Presentation of

THE EXHIBITION

“Invisible Immigrants: Spaniards in the United States (1868–1945)” is the first exhibition dedicated to the history of Spanish emigration to the United States during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

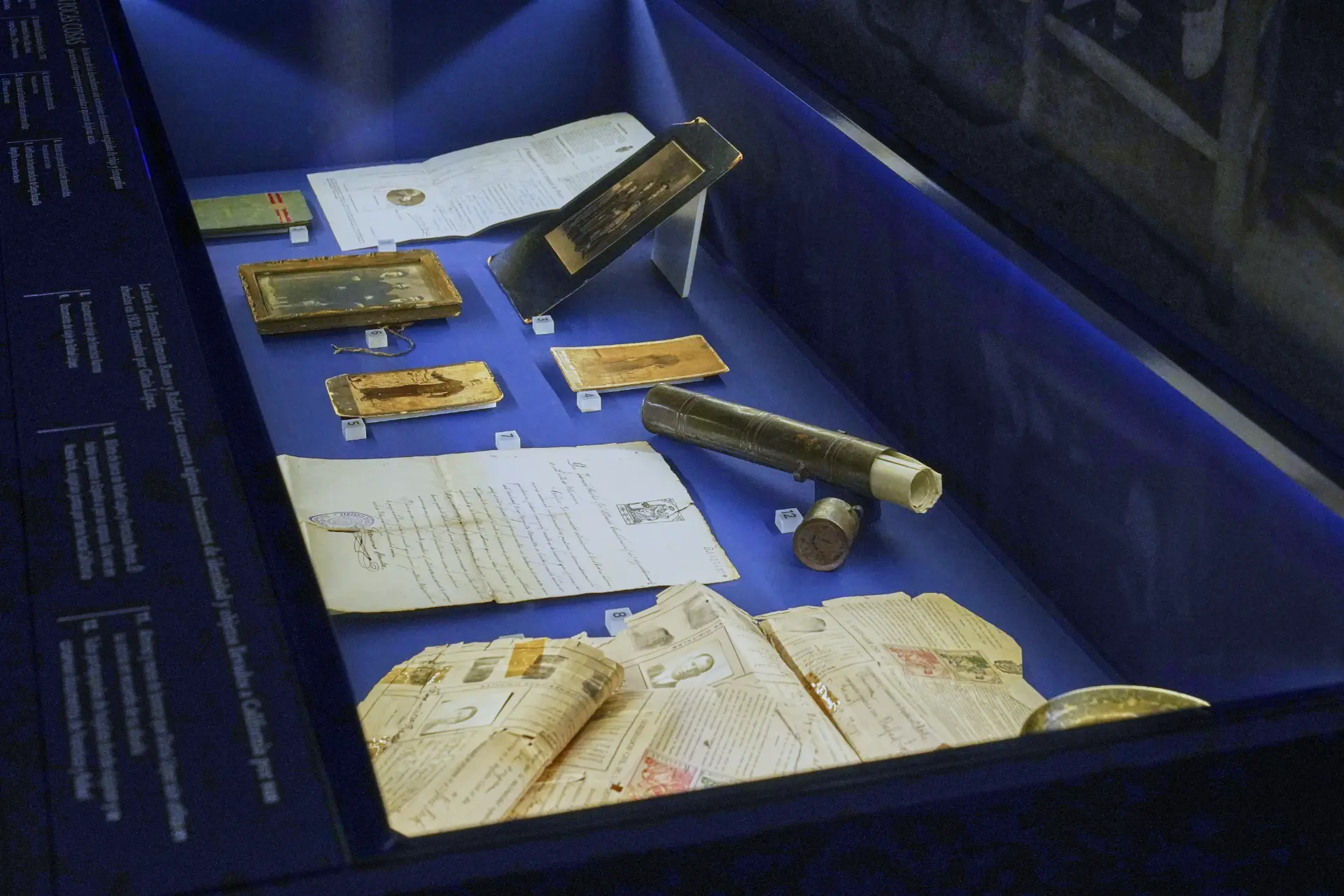

This fragile and fragmented collective epic, little known until now, has come to light thanks to more than 10 years of research by the exhibition’s curators, James D. Fernández and Luis Argeo. Together, they have assembled a valuable archive of more than 15,000 digitized images, everyday objects, home movies, and original documents from family albums and boxes of mementos treasured by the descendants of the protagonists of this diaspora.

Introduction

Divided into six chapters—Goodbye, Let’s Get to Work!, Living Life, They Organized, Solidarity and Discord, and Made in the USA—the exhibition traces the stages of the journey that any of the protagonists of this diaspora could have taken; a fascinating life and emotional journey narrated through more than 150 original and 200 digitized photographs, objects, documents, and audiovisual material:

1

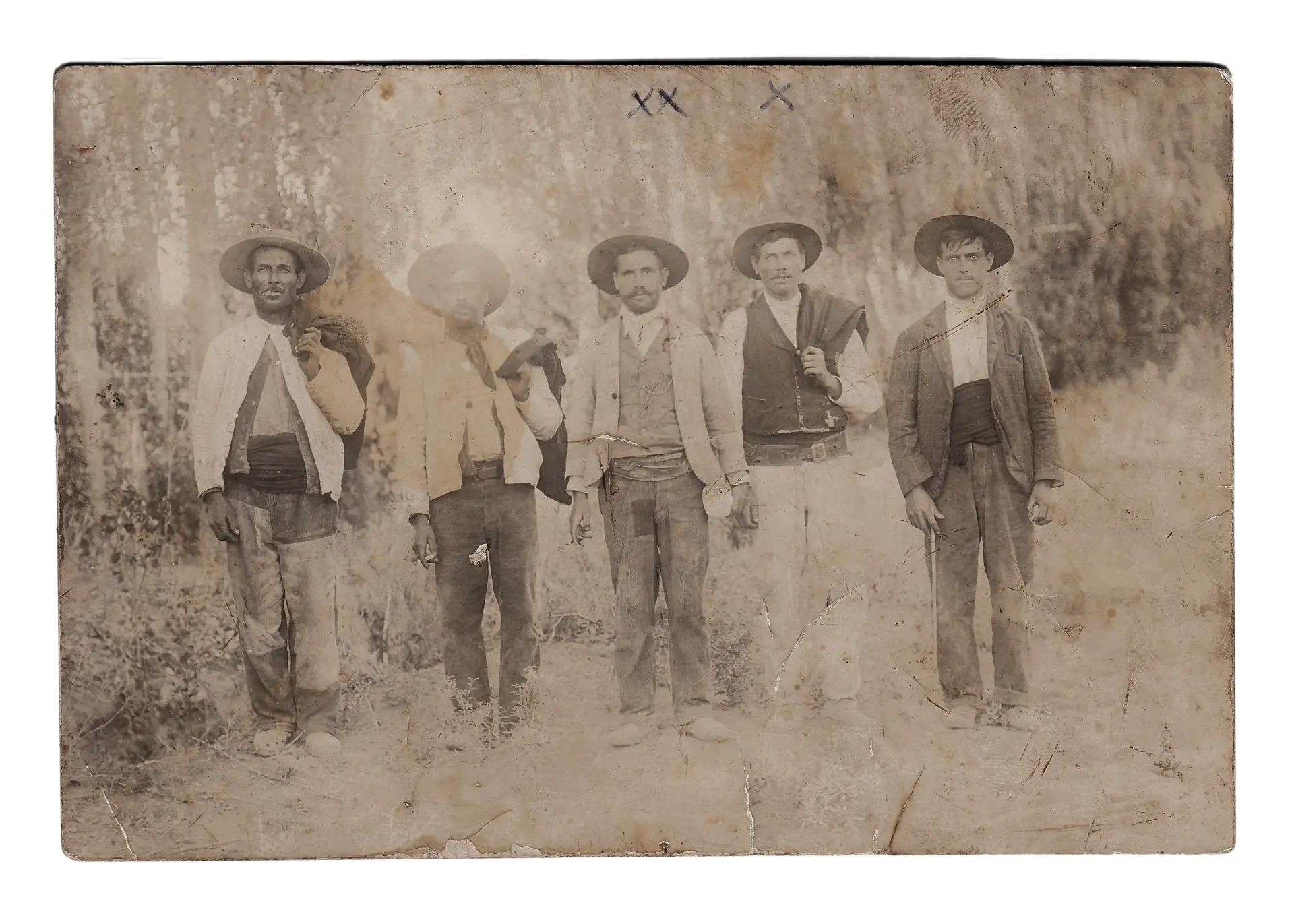

Goodbye

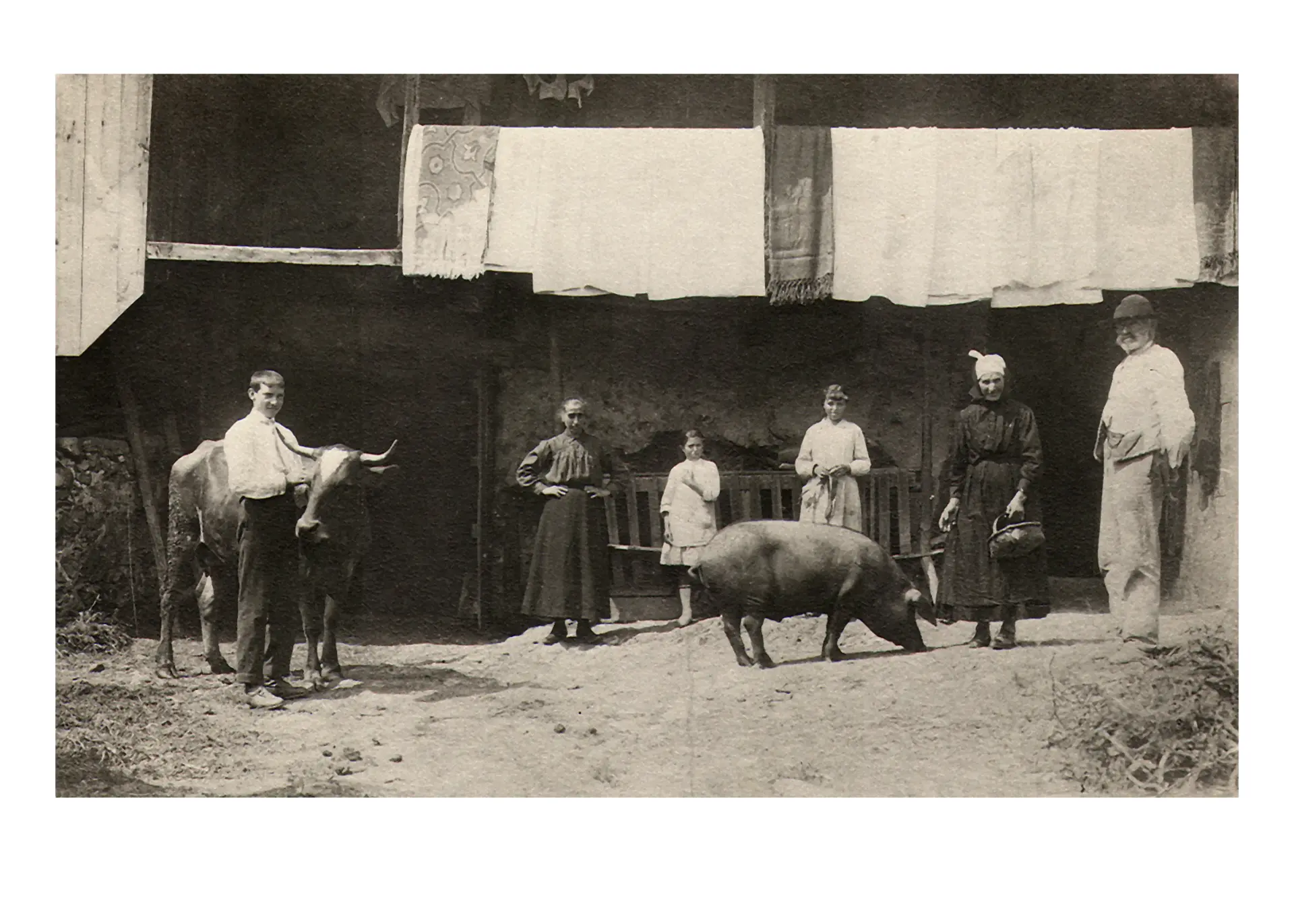

Even though it was expensive, on the eve of their departure they would have photographic portraits made of themselves and their loved ones. In the XXth century, passport photos would become a requirement; but they often commissioned these photos to leave behind an image of the prodigal son or daughter who promised to return, or to take with them a memento of those they were leaving behind. These itinerant photos abound in family archives; they were once forms of ID, or signs of life, proof of being alive.

2

NOW GET TO WORK!

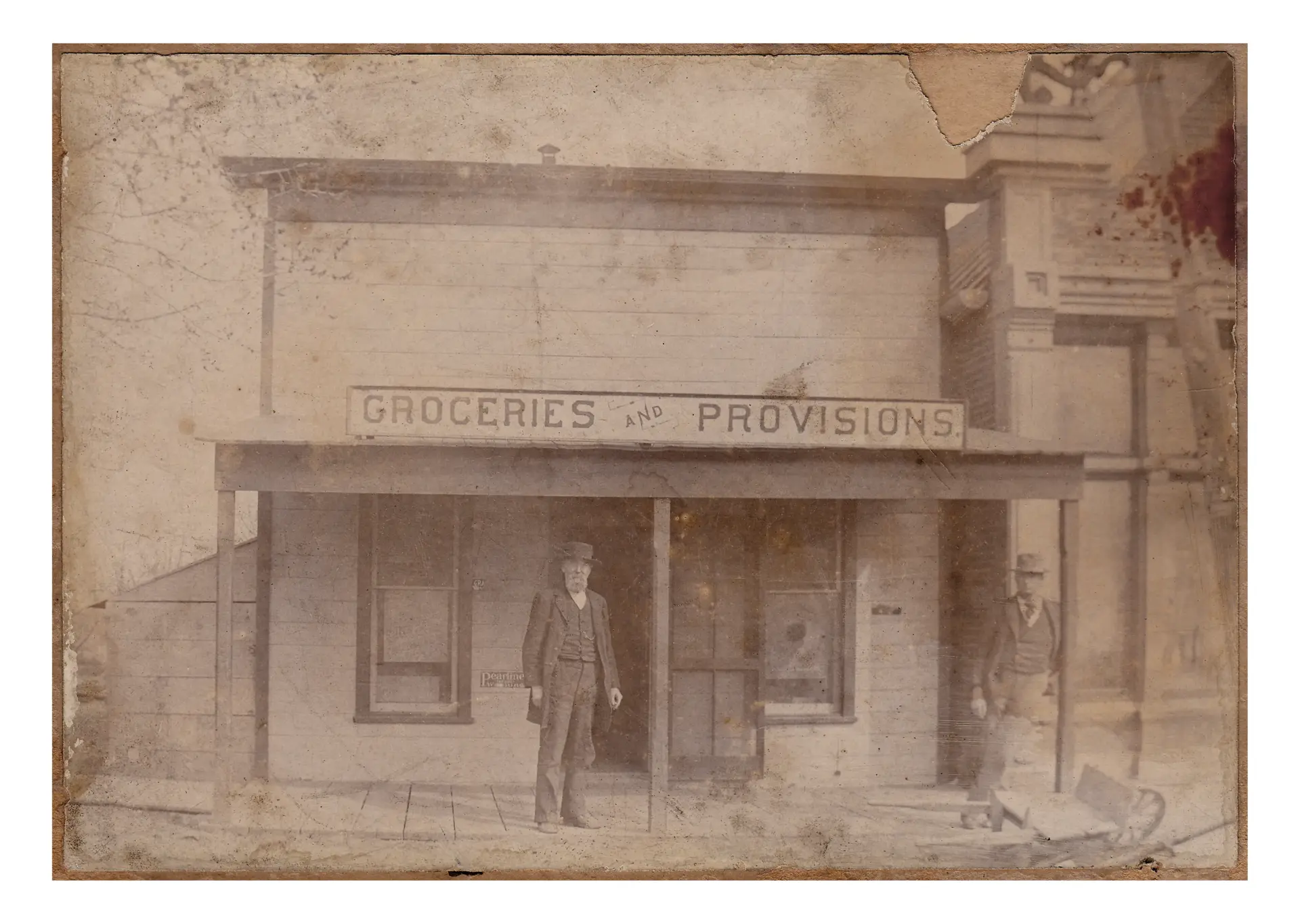

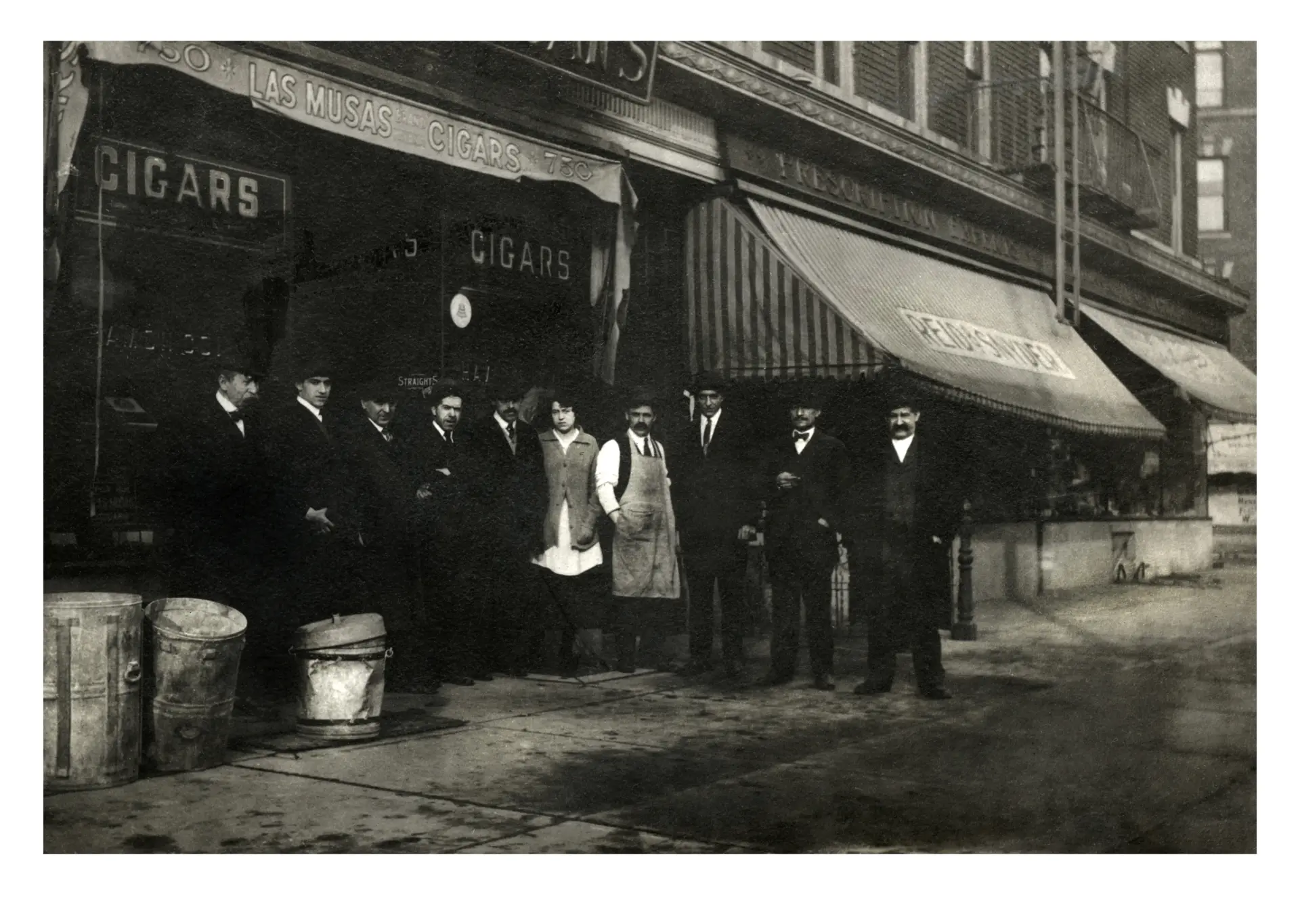

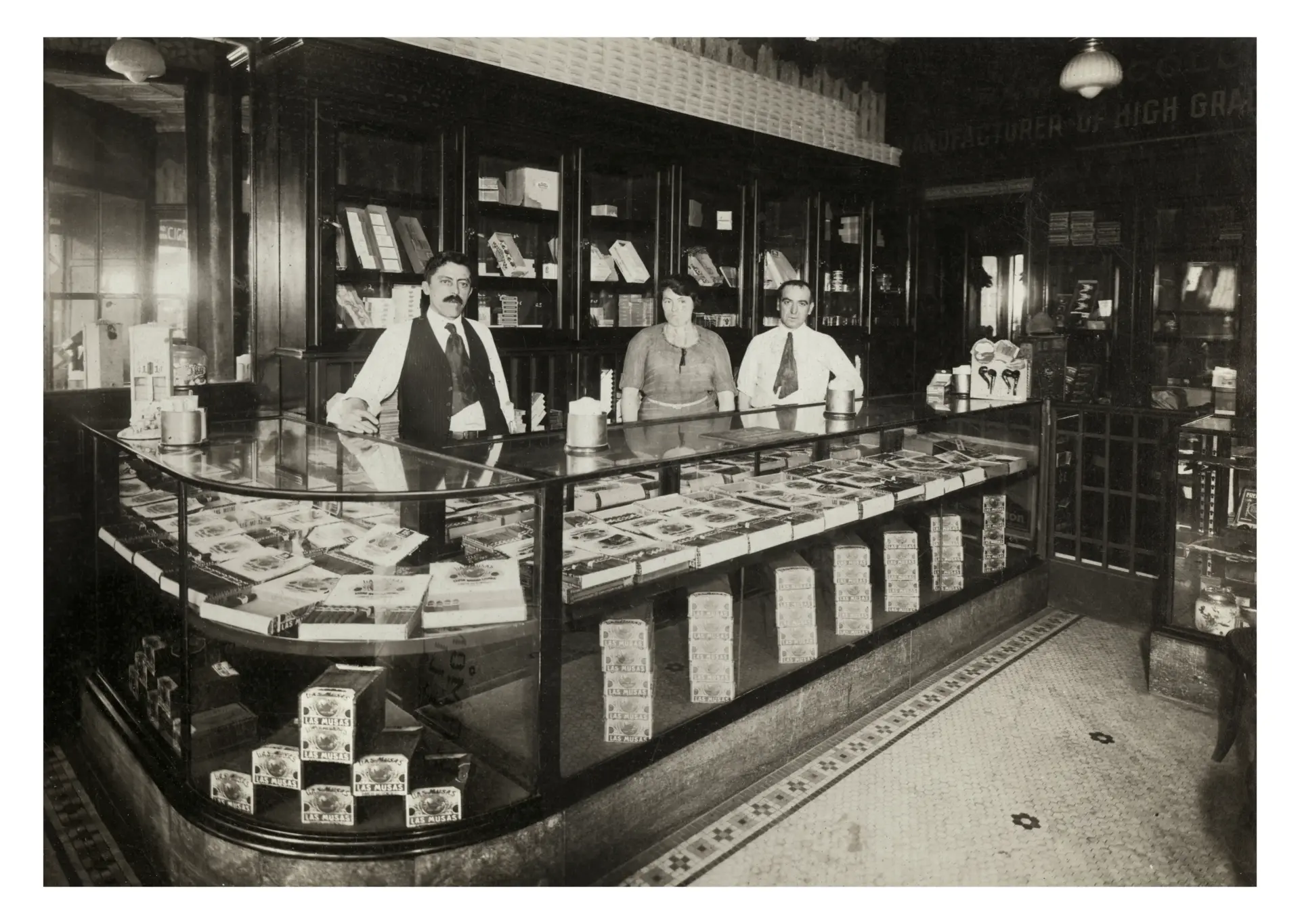

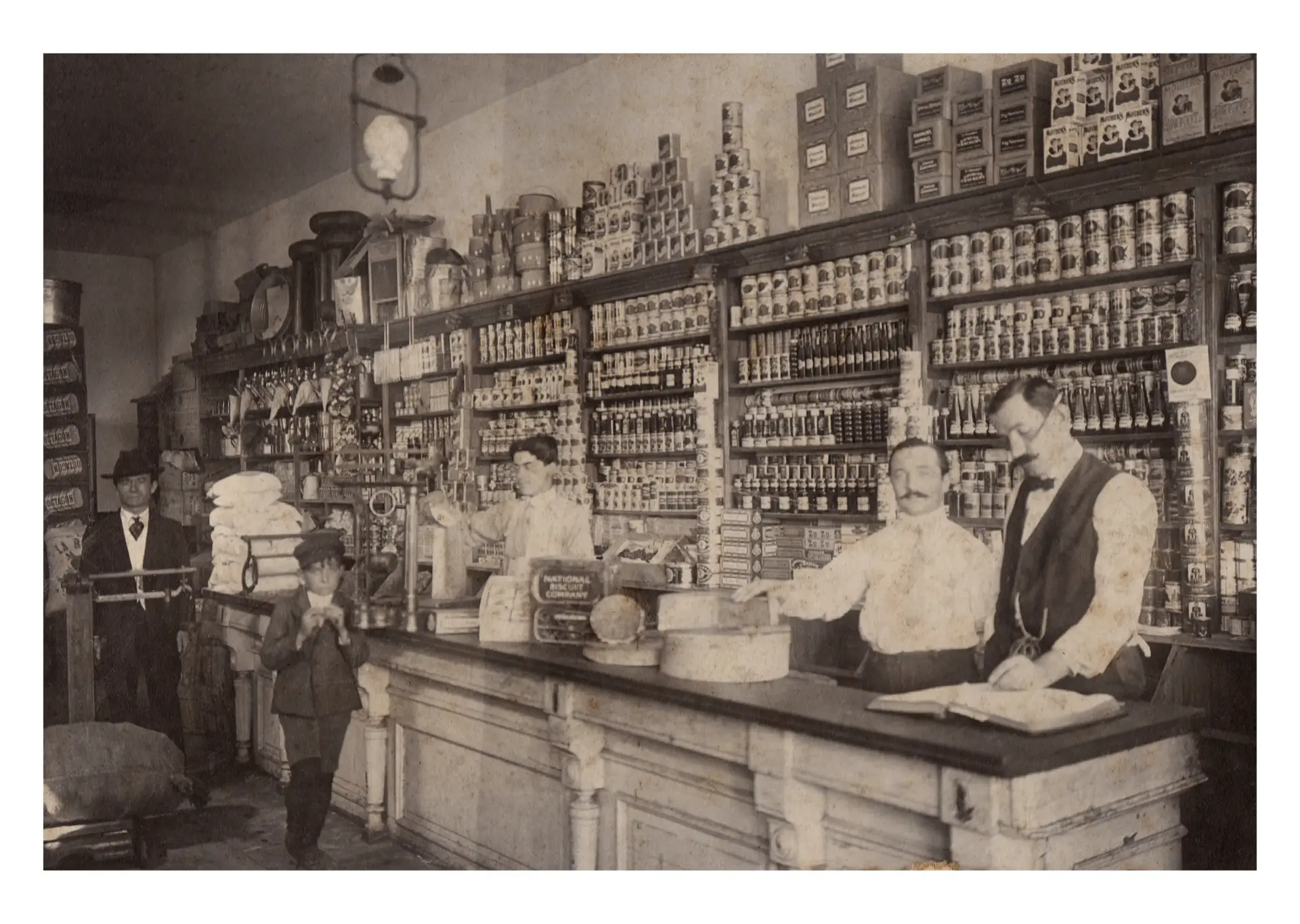

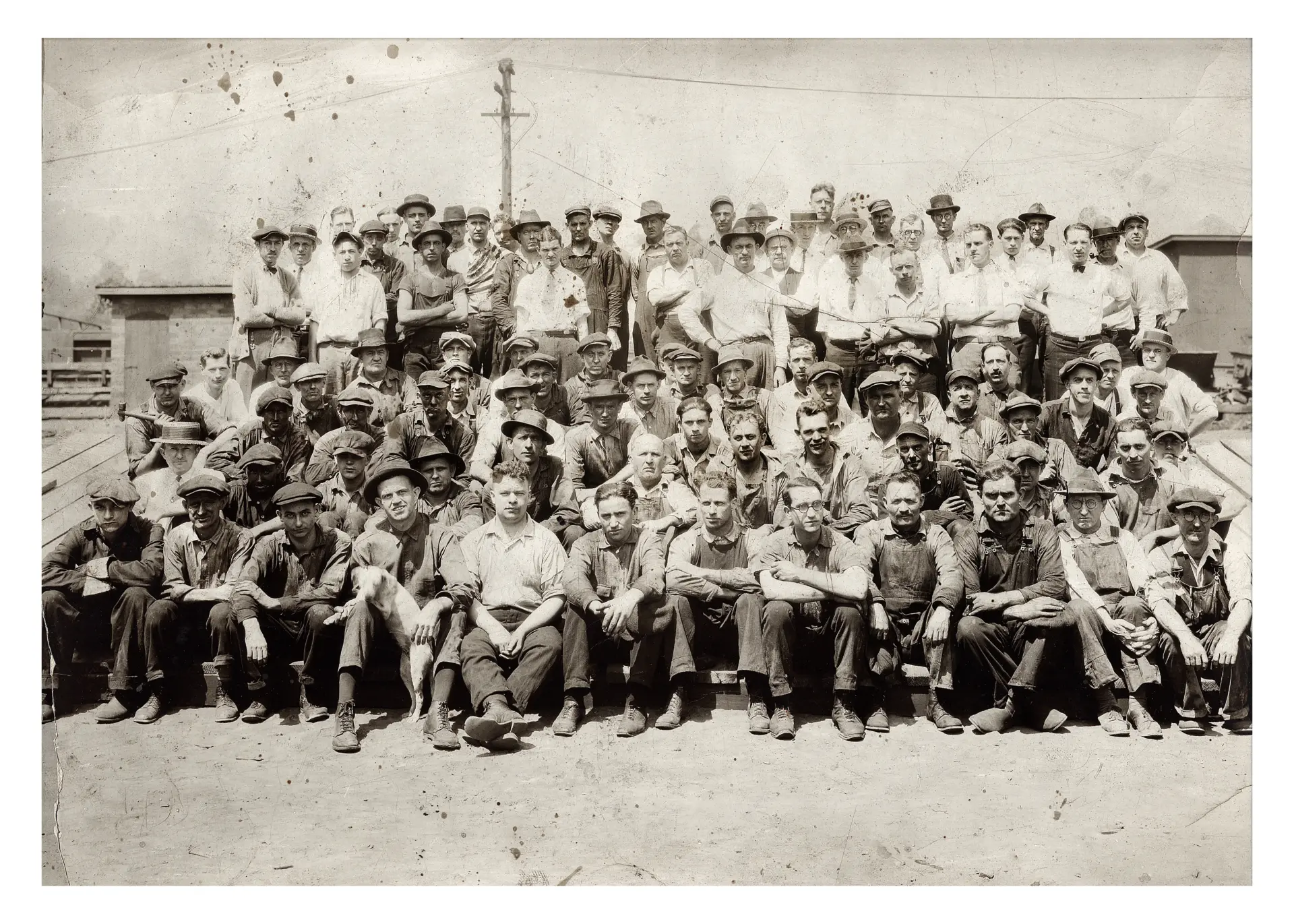

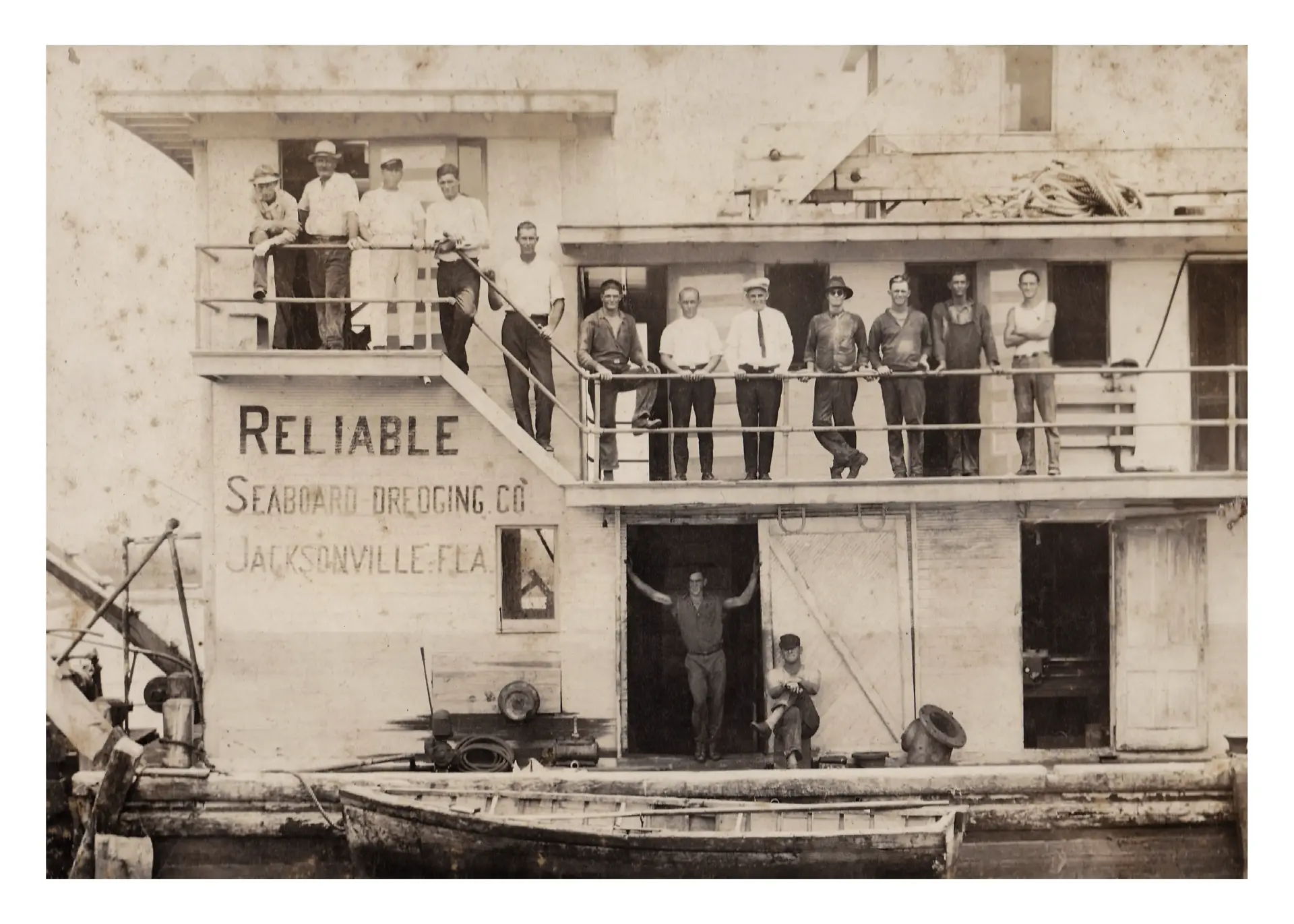

They crossed the ocean in search of opportunities, and they arrived in a strange country inhabited by millions of immigrants of almost every nationality. The Spaniards were but a drop in this new sea of workers. They began weaving informal networks, gaining a foothold in specific parts of the US, almost always centered on a type of work or an economic sector. Once established, they would call for relatives and neighbors to join them in that place, in those jobs.

The photographs that have reached us allow us to see the grocery stores, inns, restaurants and other small businesses run by and for the Spaniards wherever they settled.

3

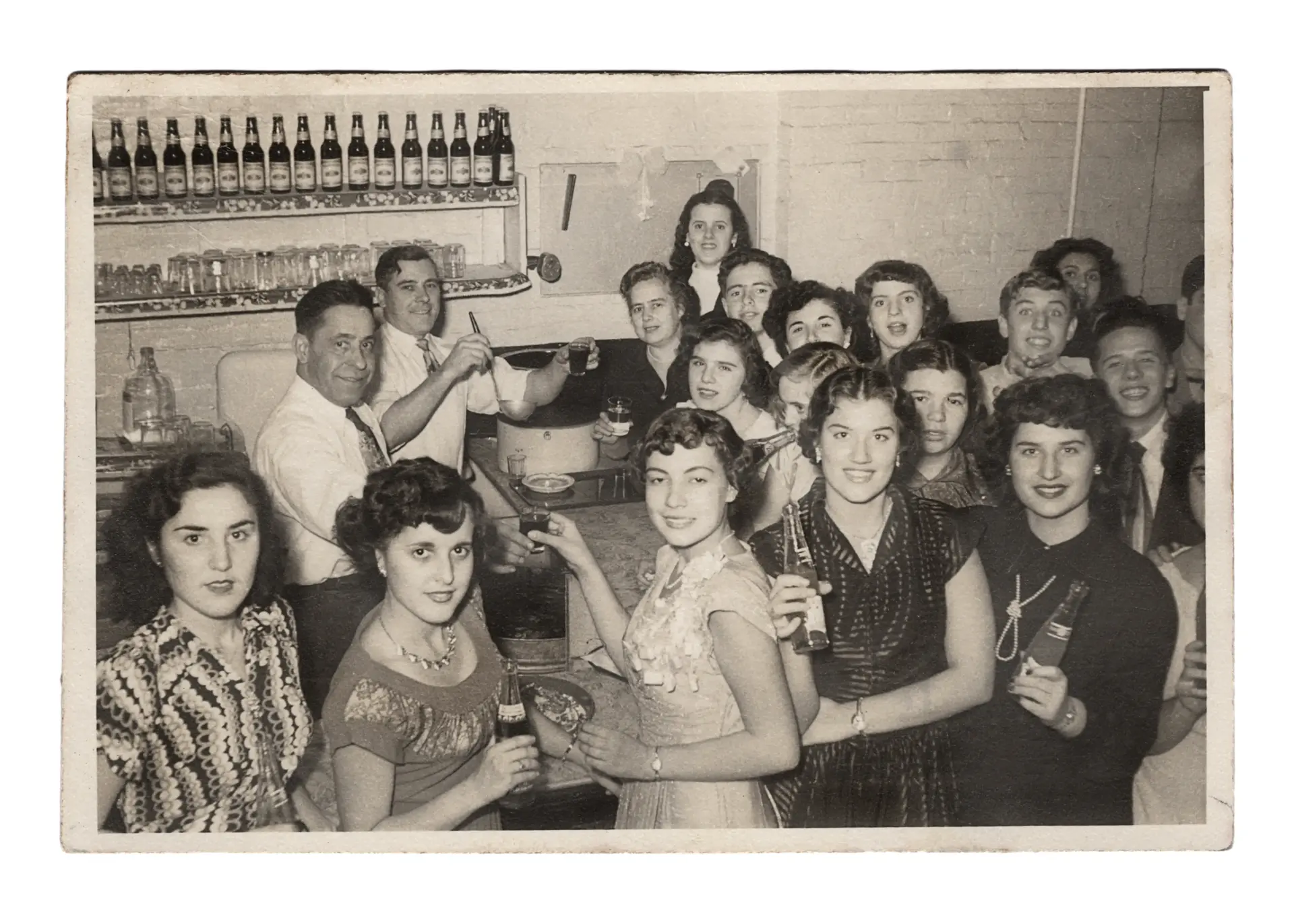

LIVING LA VIDA

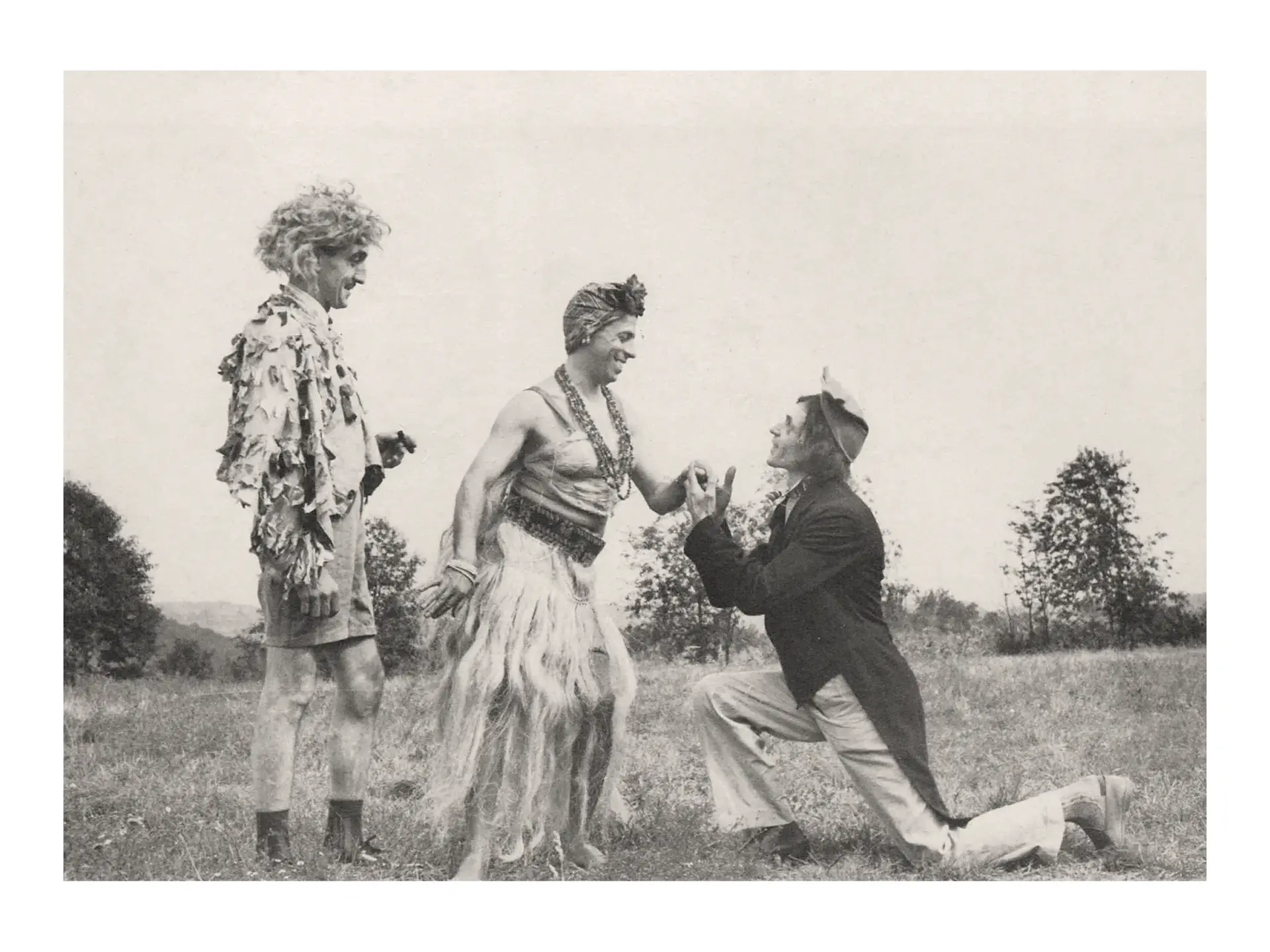

With the passage of time and some good fortune, they leave behind the worst hardships and poverty. Surrounded by their compatriots, at home or at other social meeting points, there were many moments that have to be immortalized with a snapshot: their first automobile, a special dance, a picnic, another baby in the family… In these photographs the Spaniards often display a photogenic look and smile that they seem to have acquired along the way.

The mail brings news from Spain, maintaining the links between their old and new homes, and fanning their hopes to someday return. The “americanos” wire back to Spain the money they are saving –even during the Great Depression– and they send all kinds of images –snapshots, postcards, studio portraits. Are they wearing their normal clothes, or have they donned a costume of the happy and prosperous immigrant on loan from the photo studio wardrobe?

4

THEY GOT ORGANIZED

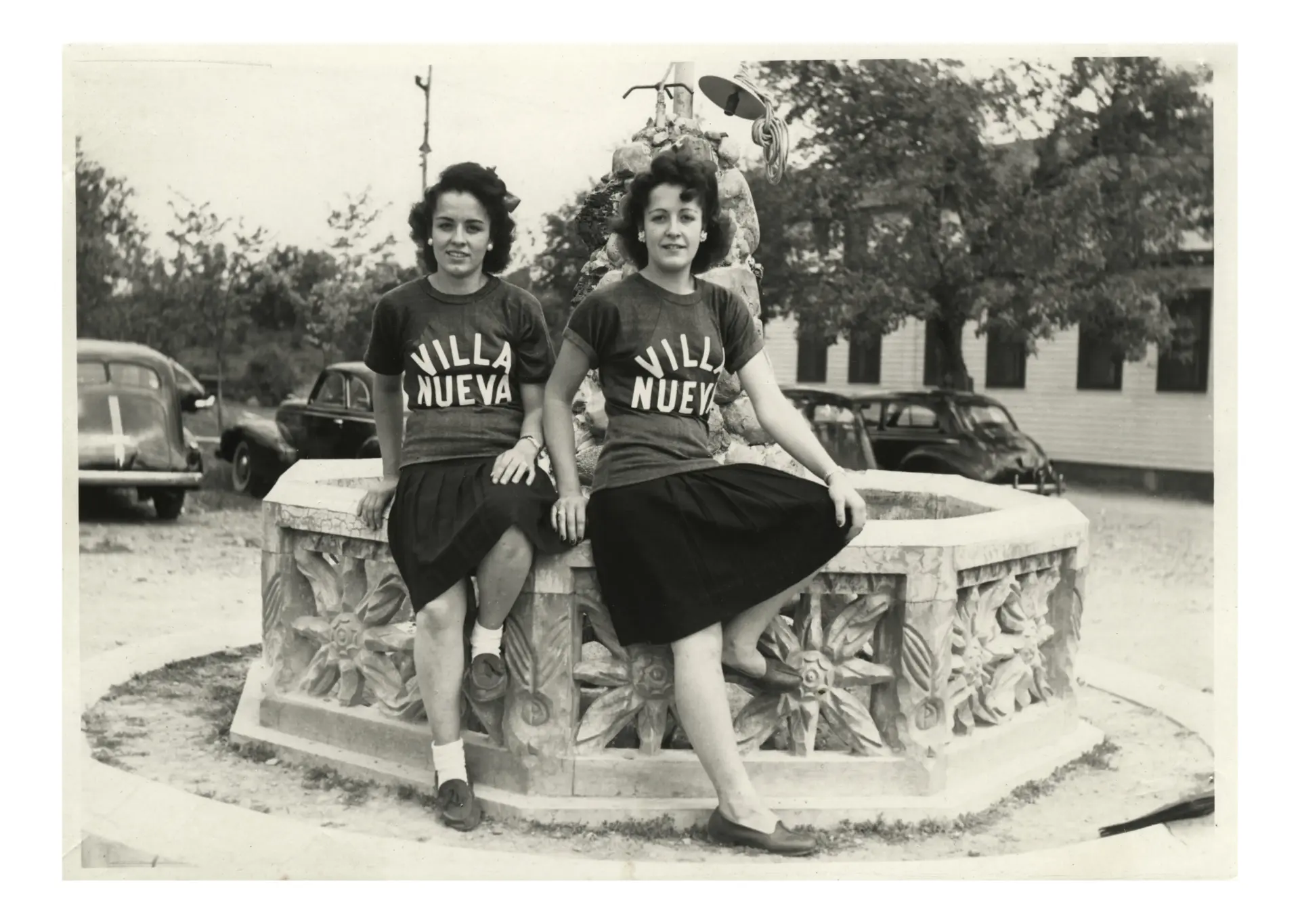

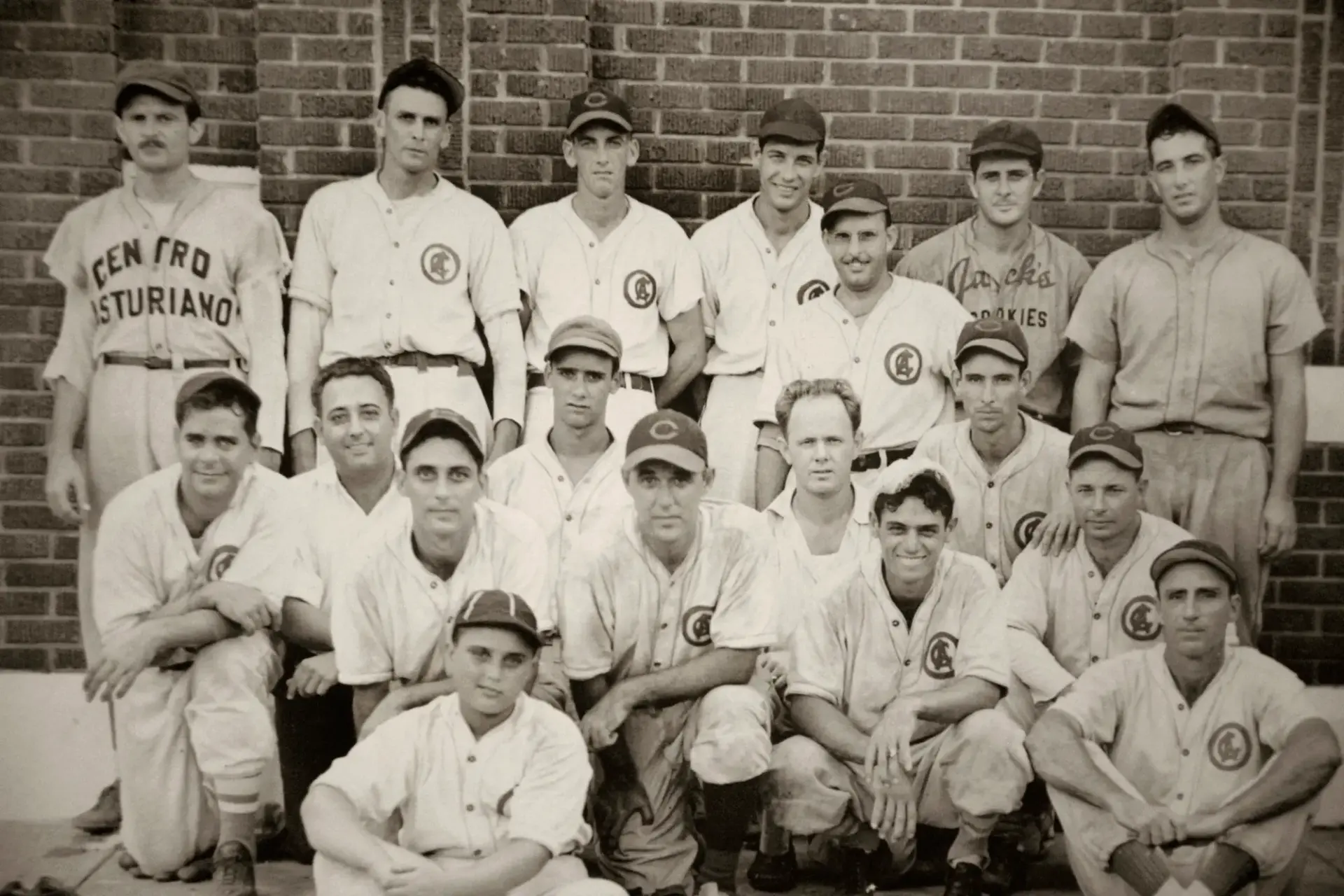

To survive the rigors of exile without a welfare state or social assistance, Spaniards had to help each other through solidarity. They formed associations of all kinds that structured their lives and, on occasion, even their deaths. The events of these groups—dances, dinners, pilgrimages, soccer matches—marked the social agenda of the colonies much more than any liturgical calendar, while promoting the endogamy of a community that continued to cherish, albeit increasingly faintly, the dream of returning.

A century later, their descendants tend to emphasize the individual or individualistic exploits of their ancestors; but their archives document, time and time again, a vast collective and choral history that would soon disintegrate.

5

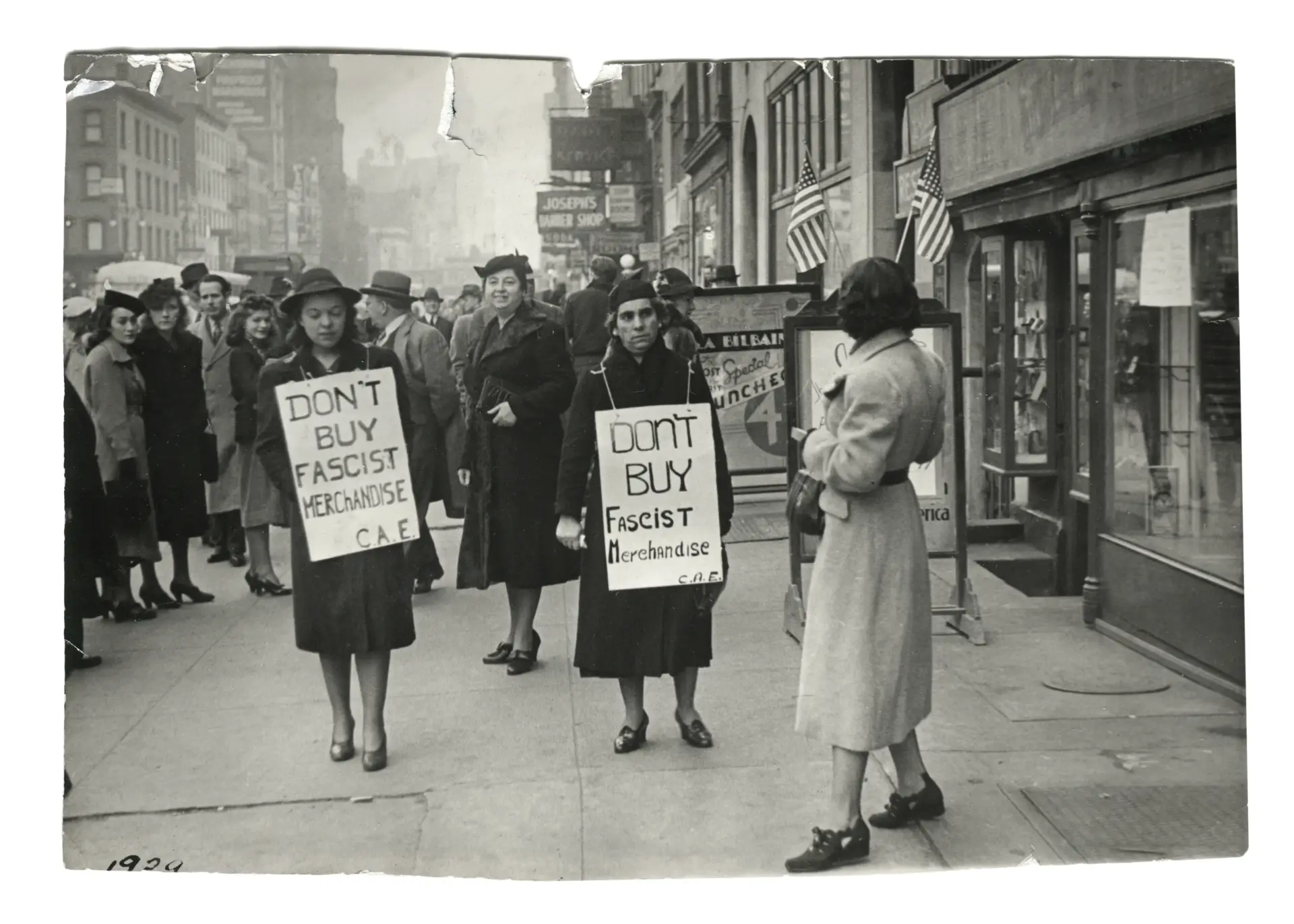

SOLIDARITY AND STRIFE

During the war years in Spain, Spanish immigrants were mostly in favor of the Republic. Thus, from July 1936 onwards, the numerous picnics, dances, and soccer tournaments organized by Spanish groups ceased to be merely social events and became ways of raising funds and support.

Family archives are full of traces of this political mobilization, although descendants are often unaware of the historical background of these images. That Republican fervor would become a problem during the dark years of McCarthyism: what was originally anti-fascism would come to be labeled as communism, which is why some people discarded or mutilated photos and documents and hid their political activism, especially from their children.

For their part, those in the United States who supported the military uprising led by Franco have left little lasting or photographic trace to share.

6

MADE IN THE USA

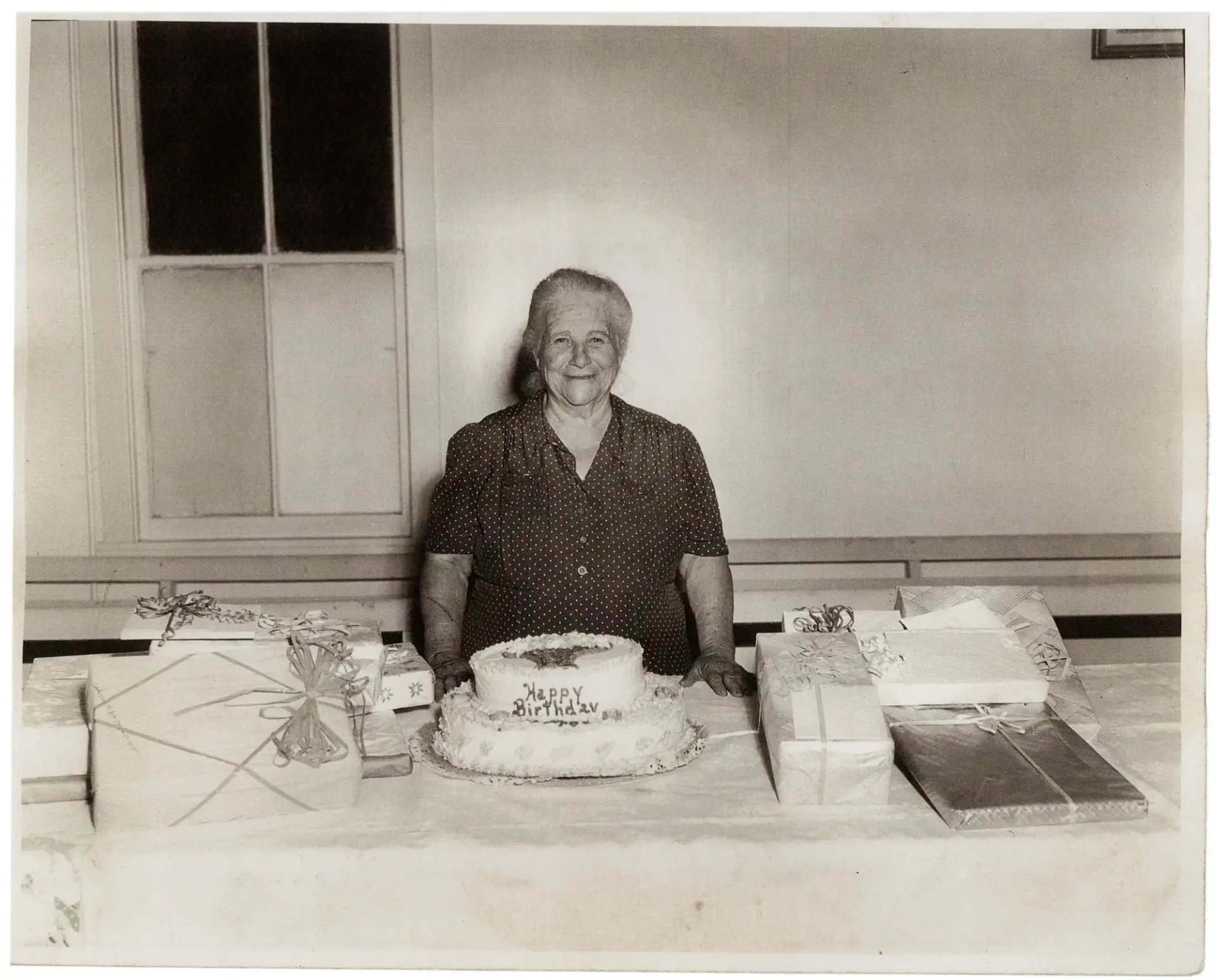

While the Spaniards had initially put all their efforts into preserving their language, customs, and endogamy in anticipation of a dream return home, the outcome of the Civil War would force them to rethink everything.

With a return to Spain ruled out in the short or medium term, adaptation to the American way of life became a part of their lives, their homes and, of course, their photographs.

Some realized that the glue that held their communities together had been hardship and the desire to return. The relative prosperity in the United States after World War II and the realization that they would not be returning to Spain acted as relentless solvents. The schooling of their children, military service, and the melting pot of cultures in which they lived would accelerate their definitive path toward assimilation and, at the same time, toward invisibility…

…until now.